Earthquake

Table of Contents

The USGS describes an earthquake as both sudden slip on a fault, and the resulting ground shaking and radiated seismic energy caused by the slip, or by volcanic or magmatic activity, or other sudden stress changes in the earth.

The movement of the earth‘s surface during earthquakes (or explosions) is the catalyst for most of the damage during an earthquake. Produced by waves generated by a sudden slip on a fault or sudden pressure at the explosive source, ground motion travels both through the earth and along its surface, amplified by soft soils overlying hard bedrock; a phenomenon referred to as ground motion amplification. Ground motion amplification can cause a great deal of damage during an earthquake, even to sites very far from the epicenter; the epicenter being the point on the Earth’s surface that is directly above the area where rock has broken on the tectonic plate below. Earthquakes strike suddenly and without warning and can occur at any time of the year, any time of the day or night.

Background

- Convergent/Destructive Plate Boundary: occurs when the two plate boundaries meet and one plate moves underneath the other.

- Divergent/Constructive Plate Boundary: occurs when the two plates’ boundaries are moving away from one another forming new crust.

- Transform Plate Boundary – occurs when two plates slide past one another.

- Convergent/Destructive Plate Boundary: occurs when the two plate boundaries meet and one plate moves underneath the other.

- Divergent/Constructive Plate Boundary: occurs when the two plates’ boundaries are moving away from one another forming new crust.

- Transform Plate Boundary: occurs when two plates slide past one another. Earthquakes are measured in terms of magnitude and intensity using the Richter Scale and Modified Mercalli Scale of Earthquake Intensity.

Extent

Measuring Magnitude

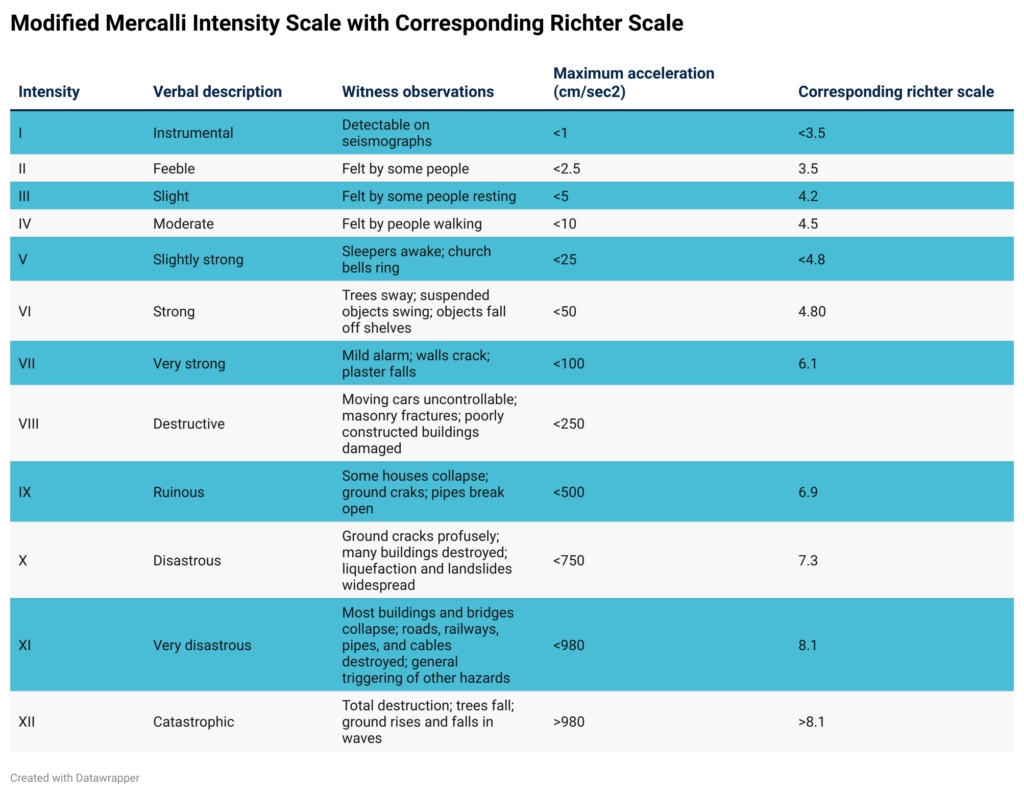

The Richter magnitude scale measures an earthquake‘s magnitude using an open-ended logarithmic scale that describes the energy release of an earthquake through a measure of shock wave amplitude. The earthquake‘s magnitude is expressed in whole numbers and decimal fractions. Each whole number increase in magnitude represents a 10-fold increase in measured wave amplitude, or a release of 32 times more energy than the preceding whole number value.

The Modified Mercalli scale measures the effect of an earthquake on the Earth‘s surface. Composed of 12 increasing levels of intensity that range from unnoticeable shaking to catastrophic destruction, the scale is designated by Roman numerals. There is no mathematical basis to the scale; rather, it is an arbitrary ranking based on observed events. The lower values of the scale detail the manner in which the earthquake is felt by people, while the increasing values are based on observed structural damage. The intensity values are assigned after gathering responses to questionnaires administered to postmasters in affected areas in the aftermath of the earthquake.

Location & Vulnerability

Faults in Kentucky

Kentucky has a variety of fault systems across the State. The two that affect Kentucky the most are in adjacent states: the New Madrid in Missouri and the Wabash in Indiana.

The New Madrid Seismic Zone (NMSZ), located in the central Mississippi Valley, is generally demarked on the north by the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. From this point in southern Illinois, the zone runs southwest, through western Kentucky (near Fulton), through eastern Missouri and western Tennessee and terminates in northeastern Arkansas, crossing the Mississippi River 3 times.

The Wabash Valley Seismic Zone which threatens southern Illinois, Indiana, and Kentucky, shows evidence of large earthquakes in its geologic history. Since 1895, The Wabash Valley Fault Zone has experienced more moderate quakes than the New Madrid Seismic Zone. Some prehistoric quakes which occurred in this zone between 4,000 and 10,000 years ago may have been larger than M6.0. Earthquake ground shaking is amplified by lowland soils, and modern earthquakes of M5.5 to 6.0 in the Wabash Valley Fault Zone could cause substantial damage if they occur close to the populated river towns and cities along the Wabash River and tributaries.

Seismic Hazard Zone

The KIPDA region is not within the New Madrid Seismic Zone or the Wabash Valley Seismic Zone. However, if a high magnitude earthquakes occur in those zones, the KIPDA region could be impacted. The KIPDA region is within a low seismic hazard zone for the New Madrid. Seismic zones delineate areas where earthquakes tend to focus, while seismic hazard zones describe areas of a particular level of hazard – such as low or moderate.

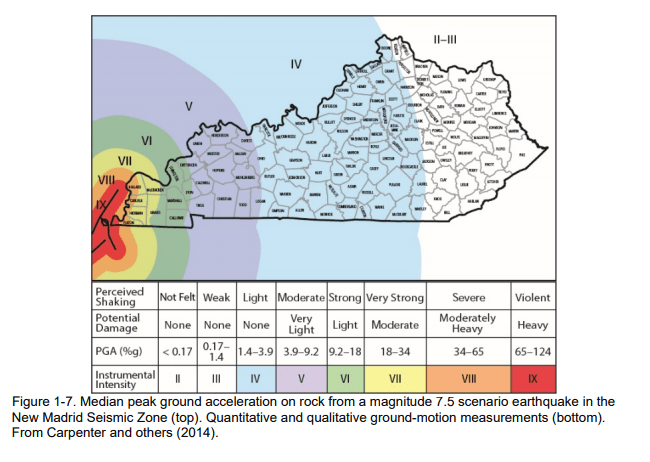

The map below is from the state of Kentucky’s 2018 Hazard Mitigation Plan. It demonstrates the median peak ground acceleration on rock from a magnitude 7.5 scenario earthquake in the New Madrid Seismic Zone [1,2]. Peak ground acceleration quantitatively measures ground motion. Essentially, the earthquake causes ground motion, which can impact areas outside of the seismic zone (i.e. moderate and lower seismic hazard zones). This causes shaking, damage, etc. The map below demonstrates that the entire KIPDA region is projected to be within the “light” perceived shaking zone and would not experience damage from a magnitude 7.5 earthquake in the New Madrid Seismic Zone.

KIPDA Region Fault Lines

The KIPDA region does have some minor fault lines and has experienced 2 earthquakes with a magnitude of 3 on the Richter scale. These fault lines and historic earthquake locations are shown on the map below.

- Earthquakes can cause widespread fire events by breaking gas lines, damaging power lines, etc. This can be further compounded because debris and fallout from the earthquake may limit access to fire fighting equipment and damage water supplies.

- Earthquakes can also damage dams or levees, which may lead to failure and subsequent flooding [3].

When a high earthquake occurs in a populated area, it may cause deaths, injuries, and extensive property damage. Earthquakes occur with minimal warning, so people’s ability to flee or prepare for such an event is limited.

Moreover, a large scale event may lead to substantial sheltering needs.

Ground shaking from earthquakes can collapse buildings and bridges, disrupt gas, electric, and phone service among other disruptions. Buildings with foundations resting on unconsolidated landfill and other unstable soil, and trailers and homes not tied to foundations are at risk of being shaken off their mountings during an earthquake.

As mentioned in the cascading effects section, earthquakes can lead to fires and dam damage. These secondary impacts can also destroy critical buildings and homes.

Earthquakes do not have a clear impact on the natural environment. However, earthquakes can damage the built environment, which could potentially lead to environmentally hazardous effects such as chemical spills, habitat destruction, etc.

Past Events + Impact

The KIPDA region has been hit by two, slight earthquakes, which have not caused any damages or injuries. Both events happened in Shelby County.

The Courier Journal reported on October 6, 2015:

A 2.7 magnitude earthquake struck about 4 miles northwest of Shelbyville Monday [October 5, 2015] at 10:52 p.m., according to the U.S. Geologic Survey. There have been no reports of damage, according to the USGS website, but the quake was felt as far west as Southwest Louisville and New Albany, Ind. As of 8 a.m., about 30 people reported to the USGS that they had felt light shaking associated with the quake. The majority of those reports came from the immediate Shelbyville area.

The Shelbyville Sentinel reported on October 9, 2019:

An unexpected event hit Shelby County early Monday morning, but it was nothing earth-shattering. A low magnitude earthquake originating in Waddy reverberated throughout Shelby County and the rest of the area. According to the National Weather Service, the earthquake was not significant, reaching a magnitude of only 2.4. “It took place at around 5:23 this morning,” said Brian Neudorff, an NWS meteorologist. “It was magnitude of 2.4 at a depth of 13.2 kilometers.”

Probability

Peak Ground Acceleration

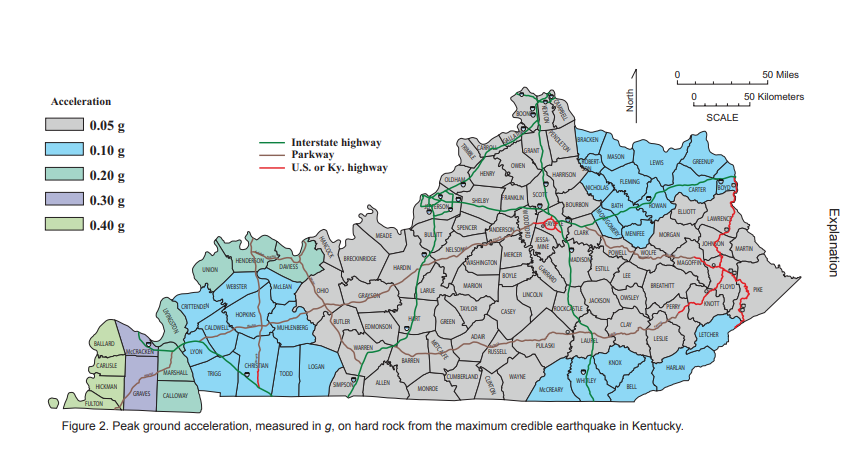

Peak ground acceleration (PGA), the acceleration due to the earth’s gravity, is one way to assess the probability of severe damage occurring following a seismic event. The higher the PGA, the greater damage is expected. The PGA reflects the best estimate (median), if the earthquake that has a maximum impact on the county occurs. Dr. Zhenming Wang, the Head of Geologic Hazards Section for Kentucky Geological Survey, developed the following map to represent PGAs across the state of Kentucky. [4]

Source: [4]

All KIPDA counties are within the .05 g acceleration zone. Therefore, KIPDA counties are unlikely to experience any shaking or damage from a maximum credible earthquake event.

Hazard Vulnerability Summary Analysis

Overall, the KIPDA region experiences low vulnerability to an earthquake event.

- Bullitt County is within the “light” perceived shaking zone for a high magnitude earthquake and does not contain significant fault lines.

- Bullitt County is the most populated county in the region and is one of the ten fastest growing counties in the state. Therefore, it has a more robust (and growing) built environment.

Because of these factors, Bullitt County experiences low vulnerability to earthquakes. Because earthquakes are non-spatial hazards, it can be assumed that this analysis should be applied to Bullitt County’s respective cities. It should be noted that Bullitt County’s cities especially Shepherdsville do contain more dense development, which makes them more vulnerable to earthquake events.

- Henry County is within the “light” perceived shaking zone for a high magnitude earthquake and contains minor fault lines.

- Henry County is predominately rural and contains the second smallest population of any county in the KIPDA region.

Because of these factors, Henry County experiences low vulnerability to earthquakes. Because earthquakes are non-spatial hazards, it can be assumed that this analysis should be applied to Henry County’s respective cities. While Henry County’s cities contain small populations (all less than 3,000 people), they do contain critical infrastructure and clusters of development, which makes them more vulnerable during an earthquake event.

- Oldham County is within the “light” perceived shaking zone for a high magnitude earthquake and contains minor fault lines.

- Oldham County is the second most populated county in the region and is one of the ten fastest growing counties in the state. Therefore, it has a more robust (and growing) built environment.

Because of these factors, Oldham County experiences low vulnerability to earthquakes. Because earthquakes are non-spatial hazards, it can be assumed that this analysis should be applied to Oldham County’s respective cities. It should be noted that Oldham County’s cities especially La Grange do contain more dense development, which makes them more vulnerable to earthquake events.

- Shelby County is within the “light” perceived shaking zone for a high magnitude earthquake and contains minor fault lines.

- Shelby County has experienced two minor earthquake events, which both demonstrated a magnitude less than 2 on the Richter scale.

- Shelby County is the third most populated county in the region and is one of the ten fastest growing counties in the state. Therefore, it has a more robust (and growing) built environment.

Because of these factors, Shelby County experiences low vulnerability to earthquakes. Because earthquakes are non-spatial hazards, it can be assumed that this analysis should be applied to Shelby County’s respective cities. It should be noted that Shelby County’s cities especially Shelbyville do contain more dense development, which makes them more vulnerable to earthquake events.

- Spencer County is within the “light” perceived shaking zone for a high magnitude earthquake and contains minor fault lines.

- Spencer County is predominately rural and contains the third smallest population of any county in the KIPDA region.

Because of these factors, Spencer County experiences low vulnerability to earthquakes. Because earthquakes are non-spatial hazards, it can be assumed that this analysis should be applied to Spencer County’s respective cities. While Spencer County’s cities contain small populations (all less than 3,000 people), they do contain critical infrastructure and clusters of development, which makes them more vulnerable during an earthquake event.

- Trimble County is within the “light” perceived shaking zone for a high magnitude earthquake and does not contain significant fault lines.

- Trimble County is predominately rural and contains the smallest population of any county in the KIPDA region.

Because of these factors, Trimble County experiences low vulnerability to earthquakes. Because earthquakes are non-spatial hazards, it can be assumed that this analysis should be applied to Trimble County’s respective cities. While Trimble County’s cities contain small populations (all less than 1,000 people), they do contain clusters of development and critical infrastructure, which makes them more vulnerable during an earthquake event.

References

[1] Carpenter, N.S., Wang, Z., and Lynch, M. (2014) Earthquakes in Kentucky: Hazards, mitigation, and emergency preparedness: Kentucky Geological Survey, ser. 12, Special Publication 17, 11 p

[2] Kentucky Emergency Management Agency (2018). 2018 Kentucky Hazard Mitigation Plan: S3-S6, Risk Assessment, Hazard Identification, 6, Earthquakes, Revised Submittal. Retrieved from https://kyem.ky.gov/recovery/Documents/CK-EHMP%202018,%20S3-S6,%20Risk%20Assessment,%20Hazard%20Identification,%206,%20Earthquakes,%20Revised%20Submittal.pdf

[3] Wood PLC (2019). Eno Haw Regional Hazard Mitigation Plan: Risk Assessment. Retrieved from http://www.enohawhmp.com/

[4] Wang, Z. (2010). Ground motion for the maximum credible earthquake in Kentucky: Kentucky Geological Survey, ser. 12, Report of Investigations 22.