Climate action

The changing climate has an affect on the frequency of natural disasters and hazards in our region. Things such as increasing temperature, drought, and air pollution all intensify the effects experienced by these hazards. It is important that we understand regional trends and analyze data in order to determine best practices and develop strategies to ensure that we can overcome the next disaster.

How are our region’s hazards impacted by climate change?

Dam Failure

In some regions, climate change is causing an increase in precipitation in the form of rainfall [1]. These changes in hydrological conditions are creating stress on dams that were not built to withstand such amounts of water. Increased rainfall and increased streamflow into reservoirs also creates an influx of sedimentation, which limits the functionality of the dam and degrades its performance [2]. As a whole, dams in the US were built between 1950-1980 and are not engineered to withstand the effects of climate change.

Combined data from the National Climate Assessment and the Army Corps of Engineers predicts that regions northeast, east and south of the Ohio River will experience an increase in precipitation in the form of rainfall by 40-50% by the year 2100. [3-4]

Drought

The results of a 2010 study on drought were uncertain for the Kentuckiana region; depending on the level of emissions released in the future, drought could either decrease or increase in frequency in the region. [5] Another 2010 study, focused on the Midwest, found much of the same. It appears as though the increased precipitation in the region will offset the possibility of drought. [6] The effect of climate change on the intensity and duration of droughts in the region is still relatively unknown. Illinois’ state climatologist, Jim Angel, thinks that the Midwest should be more worried about short flash droughts in the summer than the traditionally thought of long-term drought. [7]

Kentucky has been experiencing drought conditions more frequently in the past few years. In September of 2019, the Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet declared the entire state to be under either Level 1 or 2 drought conditions, with the Kentuckiana region being under Level 1. [8]

Extreme Cold

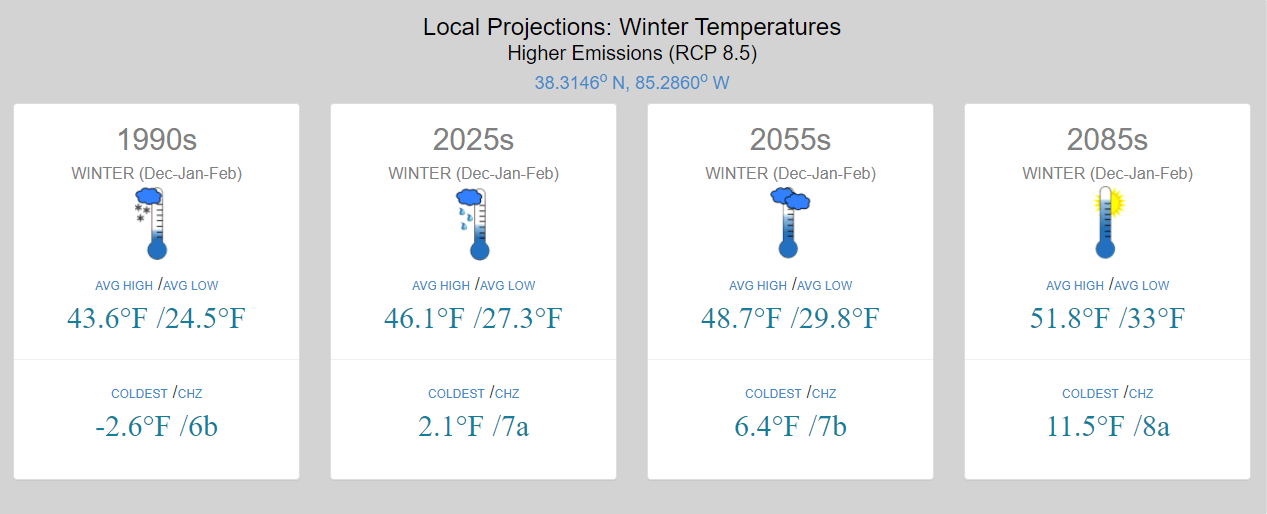

It is unclear if climate change will impact the number of extreme cold events in the KIPDA region. As shown in the graphic below, the mean temperature during winter months is increasing. Therefore, the KIPDA region can expect fewer days below freezing, but this does not necessarily translate to fewer extreme cold events. Climate change increases the frequency of unexpected, extreme events like an extreme cold event.

This graphic was generated from University of California Irvine’s Climate Toolbox site. KIPDA staff selected a general location in the KIPDA region (between Taylorsville and Shelbyville) and selected a higher emissions scenario (RCP 8.5) to develop the projection. The 1990s figure is based off of historical records for the area, while the the other temperatures are projections from University of Idaho’s gridMET dataset.

Source: Hegewisch, K.C., Abatzoglou, J.T., ‘ Future Climate Dashboard’ web tool. Climate Toolbox (https://climatetoolbox.org/) accessed on July 25, 2021.

Source: Hegewisch, K.C., Abatzoglou, J.T., ‘ Future Climate Dashboard’ web tool. Climate Toolbox (https://climatetoolbox.org/) accessed on July 25, 2021.

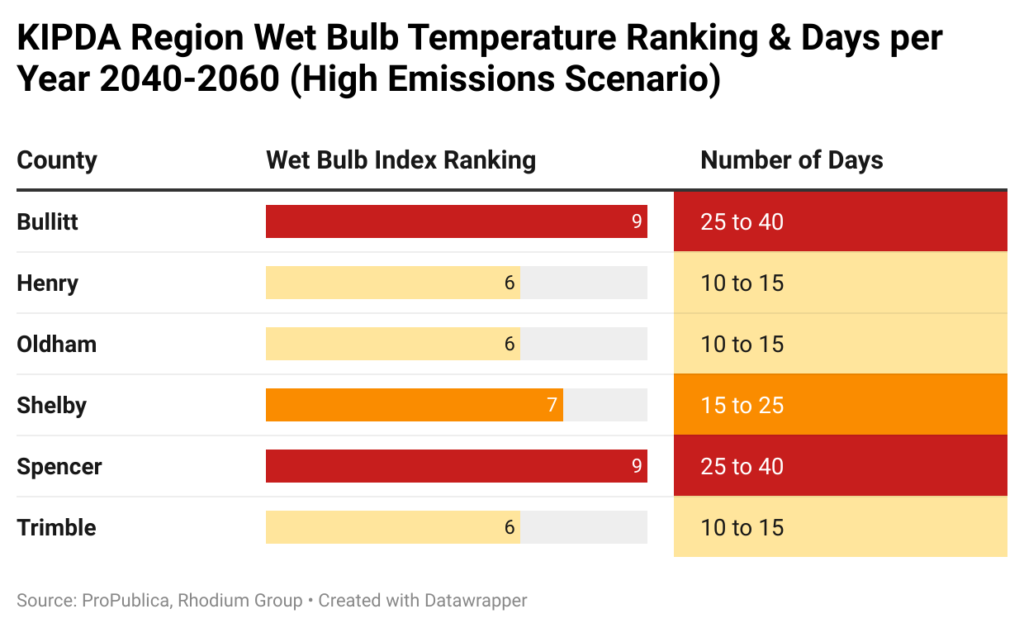

In the KIPDA region, both heat and humidity are expected to increase due to climate change. This is particularly dangerous because high humidity means that the body can no longer cool itself by sweating. The combination of hot temperature and high humidity create wet bulb temperatures. Wet bulb temperatures can make an 80 degree day feel like the hottest day in a Texas summer, which renders spending time outside not only difficult but potentially dangerous [9].

The graphic below shows the projected number of high wet bulb temperature days between 2040-2060 under a high emissions scenario. The Wet Bulb Index Rating operates on a 0-10 scale with 10 being an extremely high number of wet bulb days. In 2020, Rhodium Group and Propublica released new climate maps for the U.S., and that data is used above. Find the original source here.

Flooding

The National Climate Assessment reported that the Kentuckiana area had experienced a 10-15% increase in precipitation when comparing the 1991-2012 average to the 1901-1960 average and reported an expected increase of heavy precipitation of over 40% by 2100.

These predictions are further supported by the US Army Corp’s 2017 report where they said that flooding, drought and power failures are likely to become more common in both Indiana and Kentucky, along with the entire Ohio River Basin. [10] The Courier Journal spoke on the Army Corp’s report, saying that “…areas northeast, east and south of the Ohio River are expected to see as much as 50 percent more precipitation, with resulting higher tributary stream flows. [11]” This increased precipitation is expected to occur in the spring. In the fall, drought is expected to cause a lowering of the water level by as much as 35%.

Studies show that the occurrence of heavy precipitation is moving more towards the spring, including snowmelt. [12] [13] This will put a strain on agricultural drainage as well as increase the chance of flooding. Some simulations predict that streamflow will increase significantly in most Midwestern rivers by the 2080s, all but guaranteeing a flood. [14] The area has already been experiencing floods most likely caused by climate change. This increase in precipitation, coupled with the D+ rating on dam infrastructure that Kentucky received from the American Society of Civil Engineers, also increases the risk of dam failure. [15] The chance of floods occurring in the region are only increased by climate change, both floods caused by dam failure, and floods from undammed bodies of water.

Hail

The effect of climate change on the occurrence of hailstorms is a combination of the effects that it will have on cold temperatures and precipitation. A weakening of the polar vortex has caused cold air to be blown toward the mid-latitudinal regions of the globe, making winters colder. [16] A decrease in the amount of ice in the Arctic, coupled with the increase of atmospheric water vapor in the area, causes there to be more moisture in the air in the Midwestern United States during the winter. [17] [18] The increased amount of moisture results in more precipitation. This evidence indicates that there will be a greater occurrence of hailstorms in some areas of the United States, but the severity of those possible storms and the size of the hail is specific to each location.

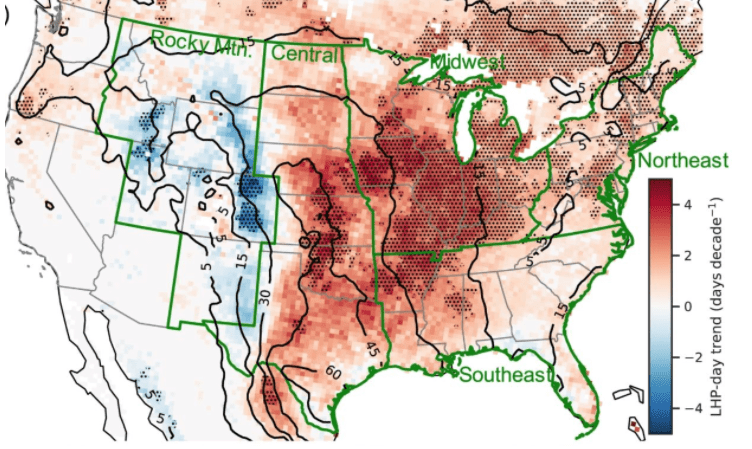

The Midwestern United States is in the region where winter precipitation is expected to increase. [19] The climate predictions given from a 2017 study, however, predict a decrease in the amount of hailstorms in the Kentuckiana region. [20] The study specifically cited Kentucky as a state where hail is expected to melt before reaching the surface in the spring. Atmospheric scientist Robert Trapp thinks that the size of hail will increase, regardless of the increase or decrease in the frequency of hailstorms. [21] A 2019 study conducted by the University of Albany also supports this claim, showing that parts of the Midwest had a 10 to 15 day uptick in the number of days with favorable conditions for large hail between 1979 and 2017. [22] The map below shows that the Kentuckiana region is one of the parts of the US with the most significant increase in large hail parameter days.

Source: Adapted from Trends in United States large hail environments and observations (2019)[/caption]

Source: Adapted from Trends in United States large hail environments and observations (2019)[/caption]

Landslide

Most landslides are caused by rainfall and snowmelt disturbing slope evolution, which in turn causes fractured rock masses to become unstable. Any way in which precipitation is increased will increase the likelihood of a landslide occurring. The way that climate change is affecting the hydrological processes of the Earth will result in an increase of landslide events in some regions.

Combined data from the National Climate Assessment and the Army Corps of Engineers predicts that that regions northeast, east and south of the Ohio River will experience an increase in precipitation in the form of rainfall by 40-50% by the year 2100. [23] [24] More rainfall in Kentucky means that the likelihood of a landslide event occurring is increased. Landslides are more prominent in Eastern Kentucky, but are also common in the Knobs and the Ohio River Valley areas, both of which are in the Kentuckiana region. [25]

Karst/Sinkhole

The research conducted on the relationship between climate change and karsts/sinkholes is still relatively small. The current available research indicates that climate change is increasing the occurrences of sinkholes. A 2017 study that collected evidence from the Fluvia Valley in Spain posited that sinkhole activity is enhanced during droughts. When the water table drops, there is less buoyant support and the weight on cavity roofs is increased, causing them to collapse. [26] The increase of drought as a result of climate change would thus increase the occurrence of sinkholes. A different case study, in Florida, conducted in 2018 yielded similar results. [27] Another aspect is the variability of the weather. As climate change increases the variability of rainfall and alters the hydrological process, the earth is bound to become more volatile. [28]

Kentucky has experienced more drought and drought like conditions in the past few years. Scientists expect the Midwest to experience more flash droughts. [29] This increase in the occurrence of drought may then lead to an increase in the occurrence of sinkholes. 55% of Kentucky sits upon karst-prone substrate. The Office of Advanced Planning and Sustainability in Louisville, KY declared that the risk of sinkholes in the city was increased although uncertain. [30]

Severe Storms

Severe storms are a combination of many different factors, such as precipitation, wind speed, and hail, which are all individually affected by climate change. Due to the higher atmospheric temperature, the air can hold more moisture and precipitation is likely to be increased in some regions. The occurrence and speed of wind is likely to rise, as well, according to a 2013 study that predicts that non-tornadic wind events will increase in frequency due to climate change. [31] The effect on hail and hailstorms is more regional specific, but the general consensus is that the size of hail will increase. The amount of research done on the effect of climate change on severe storms is limited, however, so it is uncertain exactly how that will be affected. [32]

For the Midwest, scientists expect rising precipitation to be the most concerning factor of increased severe storms, as they are mostly expected to occur in the spring. Violent winds appear to have increased for a time and now are decreasing again, but they could possible speed up again in the future as a result of climate change. [33]

The Kentuckiana region is specifically expected to have more winter and spring precipitation, so severe storms are also predicted to increase during those seasons. The effect of climate change on summer and fall events is more uncertain. Evidence on how climate change will affect the type of severe storms that produce tornadoes is also limited. [34]

Severe Winter Storms

The overall increase in global atmospheric temperature means that the air is increasingly able to hold moisture. This moisture will fall in some form of precipitation, most commonly as rain or snow, depending on the season. [35] Although some regions may get colder or experience a higher frequency of extreme cold events, they will not experience an increase in precipitation as snow. This depends on the region and its specific characteristics.

The lower Midwest and the South have experienced a decrease in the amount of snowfall during the last century. The temperatures in the Midwest and in Kentucky specifically have increased on average during the winter, but the occurrence of extreme cold events might increase. [36] [37] The 2019 cold front that swept through the region shows that the fragmentation of the polar vortex might also cause colder weather, although this may not occur every year. [38] This leaves the effect of climate change on severe winter storms in Kentucky uncertain. There is an expected increase in precipitation in the winter, but this is likely to be in the form of rain, not snow. [39] The expected and observed increase in wind chills is also a factor, as increased wind speeds would lead to more storms.

Tornado

The connection between climate change and tornadoes is uncertain.

Wildfire

The occurrence and frequency of wildfires is influenced by the occurrence and frequency of both extreme heat and drought. The rising of the average global temperature is increasing the intensity and duration at which droughts occur, meaning that there are longer periods of time where the conditions for wildfires are optimal. [40] Dry vegetation, caused by heat and lack of precipitation, fuels wildfires and forest fires, prolonging their duration and impact.

Kentucky has experienced more drought and drought like conditions in the past few years. Scientists expect the Midwest to experience more flash droughts. [41] In September of 2019 there were 107 wildfires reported by the Kentucky forestry division. September is typically a month that does not have any fires, let alone that many. It is expected that the state will see more wildfires in the summer and fall due to climate change. [42] Experts say that the state is long overdue for another forest fire, so the probability of a forest fire occurring is increasing, as well. [43]

References

[1] Lee, B., & You, G. (2013, March 20). An assessment of long-term overtopping risk and optimal termination time of dam under climate change. Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S0301479713001138? casa_token=PLqZxb118WcAAAAA%3ASgoAODu4COtOLpz40MMJuWCZWcd3l1 bKbFiqvs-5GeC2cEdc40BUM5mHnExGE6Wp4s2THmnWeg

[2] Fountain, H. (2020, May 21). ‘Expect More’: Climate Change Raises Risk of Dam Failures. Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/ 2020/05/21/climate/dam-failure-michigan-climate-change.html

[3] Hayhoe, K., Wuebbles, D. J., Easterling, D. R., Fahey, D. W., Doherty, S., Kossin, J. P., . . . Wehner, M. F. (2018). Chapter 2 : Our Changing Climate. Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: The Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II. doi:10.7930/nca4.2018.ch2

[4] Bruggers, J. (2017, December 01). Army engineers warn of brutal future for Ohio River region from climate change. Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https:// www.courier-journal.com/story/tech/science/environment/2017/11/30/ ohio-river-valley-climate-change-report/831135001/

[5] Strzepek, K., Yohe, G., Neumann, J., & Boehlert, B. (2010). Characterizing changes in drought risk for the United States from climate change. Environmental Research Letters, 5(4), 044012. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/5/4/044012

[6] Trenberth, K. E., Dai, A., Schrier, G. V., Jones, P. D., Barichivich, J., Briffa, K. R., & Shefield, J. (2013). Global warming and changes in drought. Nature Climate Change, 4(1), 17-22. doi:10.1038/nclimate2067

[7] .Mishra, V., Cherkauer, K. A., & Shukla, S. (2010). Assessment of Drought due to Historic Climate Variability and Projected Future Climate Change in the Midwestern United States. Journal of Hydrometeorology, 11(1), 46-68. doi: 10.1175/2009jhm1156.1

[8] Kratzenberg, J., & *, N. (2019, October 03). Drought declarations issued throughout Kentucky. Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https:// www.lanereport.com/117661/2019/10/drought-declarations-issued- throughout-kentucky/

[9] Lustgarten, A., Shaw, A., P., & Goldsmith, J. (2020, September 15). New Climate Maps Show a Transformed United States. Retrieved from https://projects.propublica.org/climate-migration/

[10] United States, US Army Corps of Engineers, Institute for Water Resources. (2017). Ohio River Basin: Formulating climate change mitigation/adaptation strategies through regional collaboration with the ORB Alliance. US Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved from https://usace.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p266001coll1/id/5108/.

[11] Bruggers, J. (2017, December 01). Army engineers warn of brutal future for Ohio River region from climate change. Retrieved from https://www.courier-journal.com/story/tech/science/environment/2017/11/30/ohio-river-valley-climate-change-report/831135001/

[12] Edwards, B. (2019, November 11). Galvanized by disaster. Retrieved from https://www.indianaenvironmentalreporter.org/posts/galvanized-by-disaster

[13] Did climate change cause the flooding in the Midwest and Plains? (2019, April 02). Retrieved from https:// www.yaleclimateconnections.org/2019/04/did-climate-change-cause- midwest-flooding/

[14] Bruggers, J. (2019, November 27). Climate Change In Kentucky: ‘One Home Came Floating Down The River’. Retrieved from https:// www.leoweekly.com/2019/11/climate-change-kentucky-one-home-came- floating-river/

[15] Ironcore. (2020, July 16). Kentucky. Retrieved from https:// www.infrastructurereportcard.org/state-item/kentucky/

[16] Yoksoulian, L. (2019, February 12). Are global warming, recent Midwest cold snap related? Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https://news.illinois.edu/view/6367/750060

[17] Correction for Liu et al., Impact of declining Arctic sea ice on winter snowfall. (2012). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(17), 6781-6783. doi:10.1073/pnas.1204582109

[18] Xie, Z., Black, R. X., & Deng, Y. (2017). The structure and large-scale organization of extreme cold waves over the conterminous United

States. Climate Dynamics, 49(11-12), 4075-4088. doi:10.1007/s00382-017-3564-6

[19] Hayhoe, K., VanDorn, J., Naik, V., & Wuebbles, D. (2019). Climate Change in the Midwest Projections of Future Temperature and Precipitation. Climate Change in the Midwest Projections of Future Temperature and Precipitation. Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https://www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/iles/2019-09/midwest-climate-impacts.pdf

[20] Brimelow, J. C., Burrows, W. R., & Hanesiak, J. M. (2017). The changing hail threat over North America in response to anthropogenic climate change. Nature Climate Change, 7(7), 516-522. doi:10.1038/nclimate3321

[21] Biello, D. (2007, December 05). Thunder, Hail, Fire: What Does Climate Change Mean for the U.S.? Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https://

www.scientiicamerican.com/article/thunder-hail-ire-what-does-climatechange-mean-for-us/

[22] Tang, B. H., Gensini, V. A., & Homeyer, C. R. (2019). Trends in United States large hail environments and observations. Npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, 2(1). doi:10.1038/s41612-019-0103-7

[23] Walsh, J., & Wuebbles, D. (2014). Precipitation Change. Retrieved from https://nca2014.globalchange.gov/report/our-changing-climate/ precipitation-change

[24] Hayhoe, K., Wuebbles, D. J., Easterling, D. R., Fahey, D. W., Doherty, S., Kossin, J. P., . . . Wehner, M. F. (2018). Chapter 2 : Our Changing Climate. Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: The Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II. doi:10.7930/nca4.2018.ch2

[25] Lynch, M. (n.d.). Landslide Hazards in Kentucky [PDF]. Lexington: Kentucky Geological Survey, University of Kentucky.

[26] Linares, R., Roqué , C., Gutié rrez, F., Zarroca, M., Carbonel, D., Bach, J., & Fabregat, I. (2017). The impact of droughts and climate change on sinkhole occurrence. A case study from the evaporite karst of the Fluvia Valley, NE Spain. Science of The Total Environment, 579, 345-358. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv. 2016.11.091

[27] Meng, Y., & Jia, L. (2018). Global warming causes sinkhole collapse – Case study in Florida, USA. doi:10.5194/nhess-2018-18

[28] Mathiesen, K. (2014, February 20). Are humans causing more sinkholes? Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/environment/ 2014/feb/20/are-humans-causing-more-sinkholes

[29] Kratzenberg, J., & *, N. (2019, October 03). Drought declarations issued throughout Kentucky. Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https:// www.lanereport.com/117661/2019/10/drought-declarations-issued- throughout-kentucky/

[30] Develop Louisville, Advanced Planning and Sustainability. (2020, March). Climate Change Vulnerability in Louisville, Kentucky. Retrieved from https://climatewise.org/images/projects/louisville/louisville- vulnerability-assessment-inal.pdf

[31] National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2021). Storm Events Database. [Data set]. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved from https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/stormevents/

[32] Allen, J. T. (2018). Climate Change and Severe Thunderstorms. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science. doi:10.1093/acrefore/ 9780190228620.013.62

[33] Wuebbles, D. J., Kunkel, K., Wehner, M., & Zobel, Z. (2014). Severe Weather in United States Under a Changing Climate. Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union, 95(18), 149-150. doi:10.1002/2014eo180001

[34] Molteni, M. (n.d.). Climate Change Is Bringing Epic Flooding to the Midwest. Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https://www.wired.com/story/for-the-midwestepic-looding-is-the-face-of-climate-change/

[35] Winter Storms. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.climatecommunication.org/new/features/extreme-weather/winterstorms/

[36].‘How is climate change affecting winter in my region?’ ” Yale Climate Connections. (2020, March 03). Retrieved from https://www.yaleclimateconnections.org/2020/02/how-is-climate-change-affectingwinter-in-my-region/

[37] Novelly, T. (2019, January 29). Will the polar vortex affect Louisville? Here’s what to know. Retrieved from https://www.courier-journal.com/ story/weather/local/winter/2019/01/28/polar-vortex-2019-affect-louisvillekentucky/2702488002/

[38] Hayhoe, K., VanDorn, J., Naik, V., & Wuebbles, D. (2019). Climate Change in the Midwest Projections of Future Temperature and Precipitation. Climate Change in the Midwest Projections of Future Temperature and Precipitation. Retrieved from https://www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/iles/2019-09/midwest-climate-impacts.pdf

[39] Trenberth, K. E., Dai, A., Schrier, G. V., Jones, P. D., Barichivich, J., Briffa, K. R., & Shefield, J. (2013). Global warming and changes in drought. Nature Climate Change, 4(1), 17-22. doi:10.1038/nclimate2067

[40] Kratzenberg, J., & *, N. (2019, October 03). Drought declarations issued throughout Kentucky. Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https://

www.lanereport.com/117661/2019/10/drought-declarations-issuedthroughout-kentucky/

[41] Velzer, R. (n.d.). Drought Fueling Hazardous Kentucky Wildfire Season. Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https://www.wkyufm.org/post/droughtfueling-hazardous-kentucky-wildire-season

[42] Stunson, M. (n.d.). Just a trace of rain fell in Lexington this month. Will the Kentucky drought spread? Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https://www.kentucky.com/news/local/counties/fayette-county/article235179527.htm9